Note: Many of the sites featured in this article will be explored in-person by the Sons of Wisconsin at their upcoming public event on May 10, 2025:

“The Men Who Made Milwaukee: A Walking Tour.”

In the preface to Frank Flower’s History of Milwaukee (1881), the publisher wrote, “No other city in this country has ever been so exhaustively described, with such devotion to detail or with so profuse a biographical record of its citizens.”[1] I may be biased as a life-long resident of Milwaukee, but I share the sentiment of this seemingly ostentatious claim. Milwaukee is a city with a vibrant history that in many ways is distinct from the other jewels of America’s crown. From its French discoverers to its early American pioneer spirit and German settlement, Milwaukee has been a leader of the “Forward” momentum that characterizes Wisconsin. The very name of the city, likely derived from American Indian word(s) meaning “good land” and/or “gathering place by the waters,”[2] is a testament to these claims. But like many origin stories, the “gathering” that occurred in this “good land” by “the waters” of the Milwaukee River and Lake Michigan was not without contention. The following tale of the “Bridge War” that led to Milwaukee’s establishment will provide a glimpse into America’s and Wisconsin’s frontier histories, perhaps with some implications for our modern context along the way.

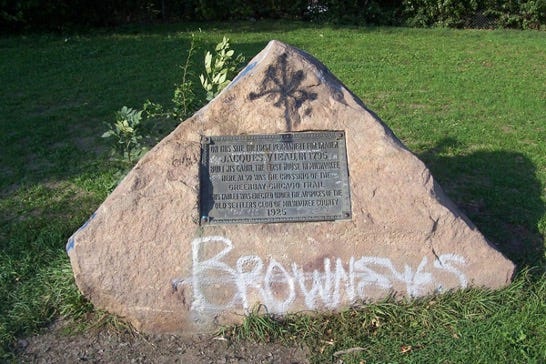

The first European explorer in what is now Milwaukee was the Rev. Jacques Marquette, S.J. (1637-1675)—after whom the eponymous Milwaukee University is named; he briefly stopped at the mouth of the Milwaukee River on October 26, 1674, although it was the Rev. Zenobé Membrau, S. J. (1645-1689) who first mentioned “the mouth of the Millioki River” in writing in 1679.[3] In the century that followed, French and English pioneers established trading posts in the Milwaukee area. One such French-Canadian fur trader, Jacques Vieau (born Le Vieaux, 1757-1852), is often credited as being the first European settler to establish a “permanent” residence in 1795 in what is now Milwaukee’s Mitchell Park (where the famous conservatory known as “The Domes” is located). However, this claim is contested by Flower, who argued that Vieau’s partner, Jean Baptiste Mirandeau (b. unknown, d. 1820/21), established a post first and became a permanent resident prior to Vieau (who had established a fur-trading network spanning south from Green Bay along the western shore of Lake Michigan. Milwaukee served as his winter base of operations to escape the harsher weather up north).

Nevertheless, the honor afforded to Vieau by later Milwaukeeans is not entirely without warrant, since it was his decision to hire the upstart Solomon Juneau (1793-1856), also a French-Canadian fur trader (and later Vieau’s son-in-law) who would go on to become Milwaukee’s first mayor.[5] But that is getting ahead of the plot—Juneau first moved to what is now Milwaukee in 1818. By 1835, Juneau’s business acumen and forward-thinking led to the establishment of “Juneautown” in what is now Milwaukee’s East Side.

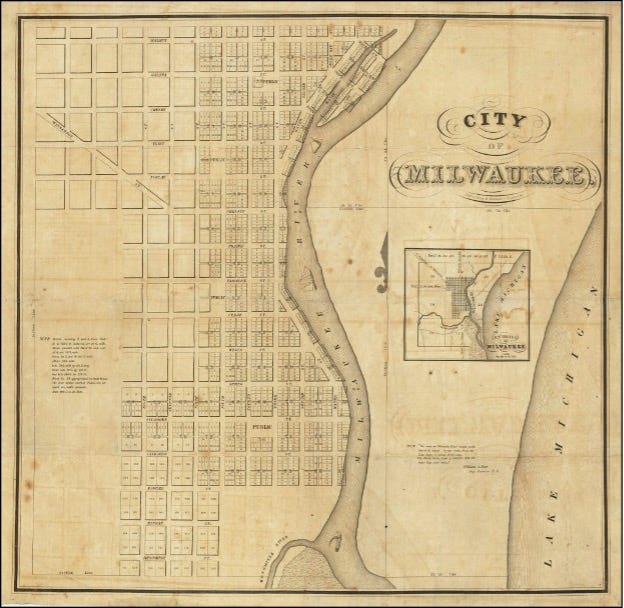

Juneau, however, was not the only man to recognize the potential of the Milwaukee region. Byron Kilbourn (1801-1870), a Connecticut-born American, also ventured into Wisconsin via Green Bay and surveyed the region on behalf of the government. He, too, came to the conclusion that the area surrounding the mouth of the Milwaukee River was full of promise. So he staked a claim to the land west of the river and established “Kilbourntown.” At the southern bank,[7] Virginia-born George H. Walker (1811-1866) built an outpost near what is now the Water Street bridge in 1834. He went on to establish “Walker’s Point,” a neighborhood and historic district of Milwaukee that bears the name to this day.

Technically, “Juneautown” and “Kilbourntown” were united by an act of the First Legislative Assembly of the Wisconsin Territory into a singular township in 1838.[10] But the legislative action was largely fictional as far as the two wards were concerned. Kilbourn in particular took a harsh view toward Juneautown, going so far as to pretend it was not even there. When he distributed maps of the region, Juneautown was conspicuously absent.

Kilbourn, the grandson of an early American inventor of the steamboat, strongly advocated transportation in the Milwaukee region and pioneered several roads, railroads, and waterways to encourage commerce and newcomers. He constructed a bridge over the Menomonee River, which allowed a direct connection to Chicago and a complete circumvention of Juneautown. His initial effort to construct the bridge was hampered in 1835 when the lumber for the project ended up in the river, which he maintained was an act of sabotage. Whatever the case, Kilbourn certainly played hardball with Juneautown thereafter. When shuttling people to his western settlement, he instructed steamboat captains to explain that the Juneautown region was an Indian trading post.[12] In fact, he completely ignored the existing system of roads already established in Juneautown and created a new grid system for the west side, the disjointed effects of which are still apparent in the angled bridges connecting roads that do not line up in Milwaukee’s downtown to this day.

Ultimately, the residents of Juneautown petitioned the Territorial Assembly to construct a bridge over the Milwaukee River at the junction of what is today Juneau Avenue (then Chestnut/Division Streets), which was followed by bridges spanning the river at today’s Wells Street (then Onieida/Wells Streets), Wisconsin Avenue (then Spring/Wisconsin Streets), and Water Street, respectively. Kilbourn staunchly opposed all but the bridge at Wisconsin Avenue, which was the favored connection point for west siders to head to the civic centers in Juneautown (e.g., the court house, etc.). Kilbourn claimed that the other bridges hampered the progress of the steamboats and schooners that docked in his territory.

These tensions reached a tipping point on May 3, 1845, when one such schooner collided with the bridge at Wisconsin Avenue. The Kilbourntown residents believed that Juneautown deliberately orchestrated an attack on the bridge they used most frequently out of spite for their disinclination to financially support the other bridges. In retaliation, the west siders demanded that the town’s Board of Trustees should remove the Juneau Avenue bridge as an ”insupportable nuisance.” [14] After a vote regarding the fate of the Juneau Avenue bridge narrowly decided against demolishing it (despite the support of both Kilbourn and Walker), on May 8th the representatives of Kilbourntown argued that they were authorized to remove the “nuisance” anyway; subsequently,angered citizens dismantled their half of the bridge at Juneau Avenue.[15] Naturally, the eastern half of the bridge toppled into the river as well. This action in turn enraged the inhabitants of Juneautown, who retaliated by aiming a cannon at Kilbourn’s westside residence from across the river, an episode that was only stopped by the last-minute revelation that Kilbourn’s daughter had died the previous day. To their credit, the Juneautown mob did not want to stoop to opening cannon fire on a grieving household.

Nevertheless, matters continued to spiral out of control, particularly when the town trustees voted to the dismantle the bridge at Wells Street in order to rebuild the bridge at Wisconsin Avenue. This understandably infuriated the inhabitants of Juneautown even further, since in this scheme only the bridge that was favored by Kilbourntown remained in-tact. As a result, on May 28 the men of Juneautown armed themselves with whatever instruments they could find and proceeded to attack the bridge at what is now Wisconsin Avenue. They also destroyed the bridge over the Menomonee River that connected Kilbourntown to Walker’s Point.

Espionage and brutality continued in the weeks that followed, which the town trustees tried to mitigate with special fines. They also applied for relief from the Territorial Assembly in the form of approval to build three permanent structures—improving upon what had been at Wisconsin Avenue and the Walker’s Point bridges and adding a new bridge site at Cherry Street. Building progress was overseen by armed guards.

The trustees further petitioned the legislative Assembly for a city charter, which would also incorporate Walker’s Point into Milwaukee. In a referendum, the inhabitants of Kilbourntown and Walker’s Point were nearly unanimous in their support of incorporating into the city (461-8), while the tensions in Juneautown resulted in a majority against incorporation (342-182). Nevertheless, the vote was successful, and the theretofore warring factions of Juneautown, Kilbourntown, and Walker’s Point were officially incorporated into one City of Milwaukee on January 31, 1846, with Solomon Juneau elected as its first mayor (an action that perhaps left the dissatisfied citizens of Juneautown feeling they had the last laugh!).

It is worth noting that both Byron Kilbourn and George Walker also went on to serve multiple terms as mayors of the City of Milwaukee. Kilbourn proceeded to found more cities, including West Bend and the Wisconsin Dells. Walker served in the Assembly, while his younger brother became one of the first United States Senators from Wisconsin. A grateful city ensured that the remains of all three men were eventually interred within the city limits. By all accounts, each of these founders was pivotal in the founding of Milwaukee and are probably worthy of their own articles at a later date. For now, it is worth contemplating what the lesson of their initial struggles and eventual unity might have to offer the Sons of Wisconsin today.

[1] Frank Abial Flower, History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin (Chicago: The Western Historical Company, 1881), p. 7f, https://books.google.com/books?id=pnAvAQAAMAAJ.

[2] Cf. Matthew J. Prigge, "What Does 'Milwaukee' Mean, Anyway?" in Milwaukee Magazine (January 29, 2018), https://www.milwaukeemag.com/what-does-milwaukee-mean/.

[3] Flower, History of Milwaukee, p. 36.

[4] Copyright © 2005 Sulfur, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, permission granted to use under the GNU Free Documentation, Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/e/ec/Jacques_Vieau.jpg.

[5] Incidentally, Juneau’s personal cook, Joe Oliver, was likely the first African in Milwaukee.

[6] Ibid., p. 49.

[7] According to Lex Renda, this was centered to the northwest of where the river, at that time, emptied into the lake. See Lex Renda, "Bridge War," Encyclopedia of Milwaukee, https://emke.uwm.edu/entry/bridge-war/.

[8] Paul Haubrich, "Class of 1839: Byron Kilbourn," Milwaukee Independent (March 20, 2016), http://www.milwaukeeindependent.com/articles/class-of-1839-byron-kilbourn/.

[9] See Bethany Harding, "George H. Walker," Encyclopedia of Milwaukee, https://emke.uwm.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/GeorgeWalker_01-2156x3024.jpg

[10] See “Acts Passed by the First Legislative Assembly of The Territory of Wisconsin,” https://docs.legis.wisconsin.gov/1838/related/territory_acts/56.pdf

[11] See "The first printed plan of Milwaukee Wisconsin," Boston Rare Maps, https://bostonraremaps.com/inventory/kilbourn-lapham-milwaukee-wisconsin-1836.

[12] Matthew J. Prigge, “Bridge Wars,” Shepherd Express (April 7, 2014), https://shepherdexpress.com/culture/ae-feature/bridge-wars/.

[13] See "Map of Milwaukee," Barry Lawrence Ruderman, https://www.raremaps.com/gallery/detail/68734/map-of-milwaukee-population-in-1835-none-in-1843-6068-lapham.

[14] See Prigge, “Bridge Wars,” https://shepherdexpress.com/culture/ae-feature/bridge-wars/.

[15] See Renda, “Bridge War,” https://emke.uwm.edu/entry/bridge-war/.